While we have been on lockdown there have only been a very limited number of walks I have been able to take. I have walked around my house. Lately I have walked down town to do some shopping. I have gone on some walks around our local park. The journey I have done most frequently and taken most pleasure in has been to walk to the end of our street, cross the road, and walk along the path though the fields. It makes a circle of about 2 miles. I have walked this on sunny days and under heavy, threatening clouds. From early spring to mid summer. I often carry a camera or my phone. I take random pictures but have not previously been organised about this.

I decided that I would try an experiment. I took my Instax Square and allowed myself 10 prints. A whole cartridge. I admit that I did take rather more images as it needed some experimenting. Previously I have only used the Instax for images of people and the lens is wide angle, very suitable for close ups of people – but you get rather more than expected on a distance shot. There is no focus control or choice of f-stop or shutter speed. Point, shoot and hope.

The idea came from the images of Paul Gaffney in Perigee (Gaffney, 2017) who first went walking with his Polaroid to explore the area before going back under moonlight – but ended up using them as part of the project. I have also recently looked at the work of Laura Letinsky who also used a Polaroid camera for planning images, and then, when they were old and distorted (and somehow strangely beautiful) published them in Time’s Assignation and Other Polaroids (Letinsky and Herschdorfer, 2017).

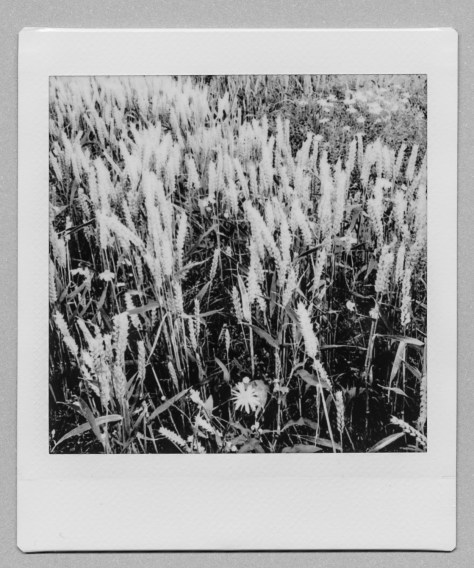

The Instax allows for either automatic printing, just as taken, and on the spot, which could work out very expensive, or for manual printing at a later date. If you chose manual printing you have the choice of several filters, one of which is monochrome. I decided to print a set of 10 monochrome images that took me on a walk around the circle, starting with the signpost and ending up with the telegraph post at the end of the path. En route I saw sky and clouds, barley and wheat, thistles (very Scottish) and Rosebay Willowherb, paths and trees. It was difficult to reduce the selection to 10.

For showing on here I am scanning the original prints. I could take the images from the SD card and put to Lightroom and use from there but I would be tempted to fiddle, and it would loose the effect of the white surround that mimics the old Polaroids, which I like and wanted for this series. The scanned images show the idea of the series but they are not as crisp and do not have the sheer tactile pleasure of looking at the images in the original prints. It is interesting using only the 10 images that you get from one cassette, making the choice and no going back.

Images:

I have just attended a zoom ‘Write where you are’ and used this path as a subject. This is what I wrote:

The path is at the end of my street. In winter it is bleak. The trees are bare, the fields are empty. The sky is heavy, but you can see for miles. Spring comes late here. Yellow flowers along the edges. The earth breaks into shoots. What has the farmer planted this year? Summer changes again. The path is surrounded by tall grasses, by cow parsley and rosebay willowherb. The colour has changed to white and pink. The fields grow barley and wheat. Barley for whisky, wheat for bread. The two essentials. Last year it was oilseed rape, heavy yellow smells. Soon autumn comes. The fields will turn green to gold. The cycle turns. Sometimes there are poppies but not this year. I will walk again tomorrow and look for the deer, listen to the birds. Be free.

The words tell the other half of the story about theplace.

References:

Gaffney, P. (2017) Perigee. Ireland: Self-published.

Letinsky, L. and Herschdorfer, N. (2017) Time’s assignation. Santa Fe: Radius Books.