The Brief: Shoot a series of 5 subjects who are unaware of the fact they are being photographed. Think through carefully. Be aware of other people’s feelings and also any privacy laws.

I was aware that this was potentially a difficult exercise as I find taking portraits hard and am not often in places that there are a lot of people other than at work. Work was not an option as there would be ethical issues involved as I work in a hospital. I decided to make use of the opportunity to take images at the Edinburgh Festival as:

- Just about everyone was carrying and using either a camera or a smart phone

- The Royal Mile (which runs though the centre of Edinburgh) has endless people walking up and down it, and a series of free outdoor events that you can sit and watch

I went to Edinburgh on a sunny day, by myself. On reflection, it might have been better to take someone with me for company and so that I didn’t stand out so much, although there were plenty of other single people there. I spent the day wandering up and down the Royal Mile, finding places where I could sit or stand to people watch and take images. Most of the time people were so involved in the general buzz that they did not notice me taking pictures and most of those who did just smiled at me. Some posed! There was one difficult incident when I was approached by a large and aggressive man, himself carrying a large camera with a very long lens, who said that I should not be taking pictures of anyone else without their explicit permission, as it was rude, illegal, and gave professional photographers like himself a bad name. He went on to say I was obviously a member of a camera club who thought I was being clever. I did not observe him going up to anyone to ask their permission to take photographs and he was not wearing any name badge or obvious identification.

When I got home, I sorted my images. As I did not have the opportunity to examine them while I was in Edinburgh and would not have been able to repeat the exercise, I had relied on taking a large number of images and had ended up with over 400! Many were out of focus or did not really show anything; people had stepped in front of me, bumped into me or moved away at the critical moment.

On examination they divided up into groups:

- General crowd scenes

- The performers

- People watching the performances

- People chatting to each other

- People staring intently into their smart phones, often taking selfies

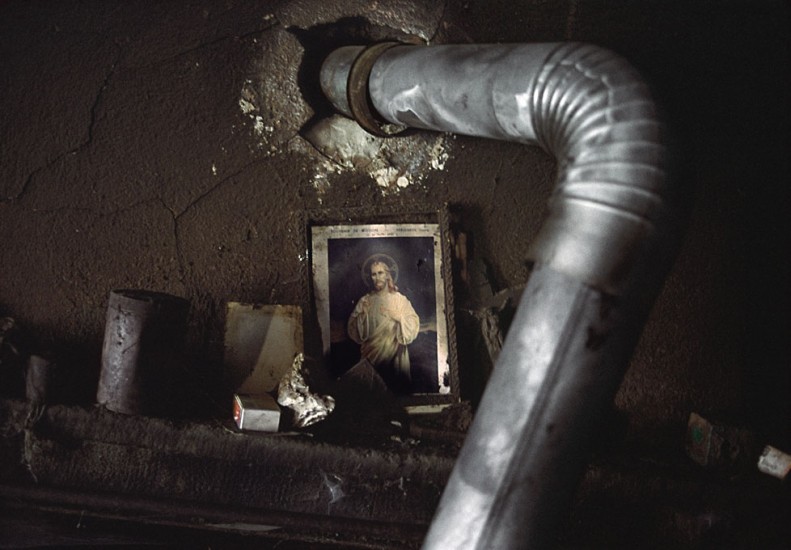

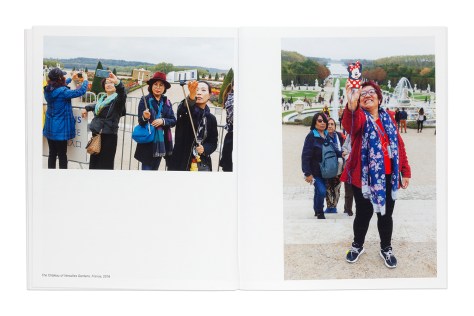

This gave me a large number of possibilities to work with. The most interesting two groups of people were the people watching the performers and the phone addicts. As I have spent some time over the course looking at the subject of people taking images of other people taking pictures, such as Martin Parr and Martin Parr and Paul Reas , I decided to follow their example and look at the images of people taking pictures.

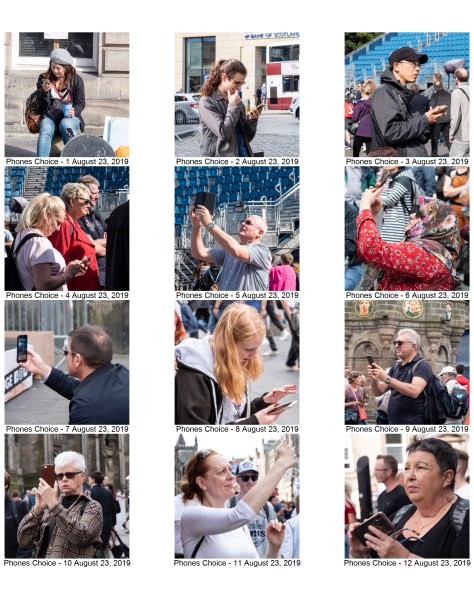

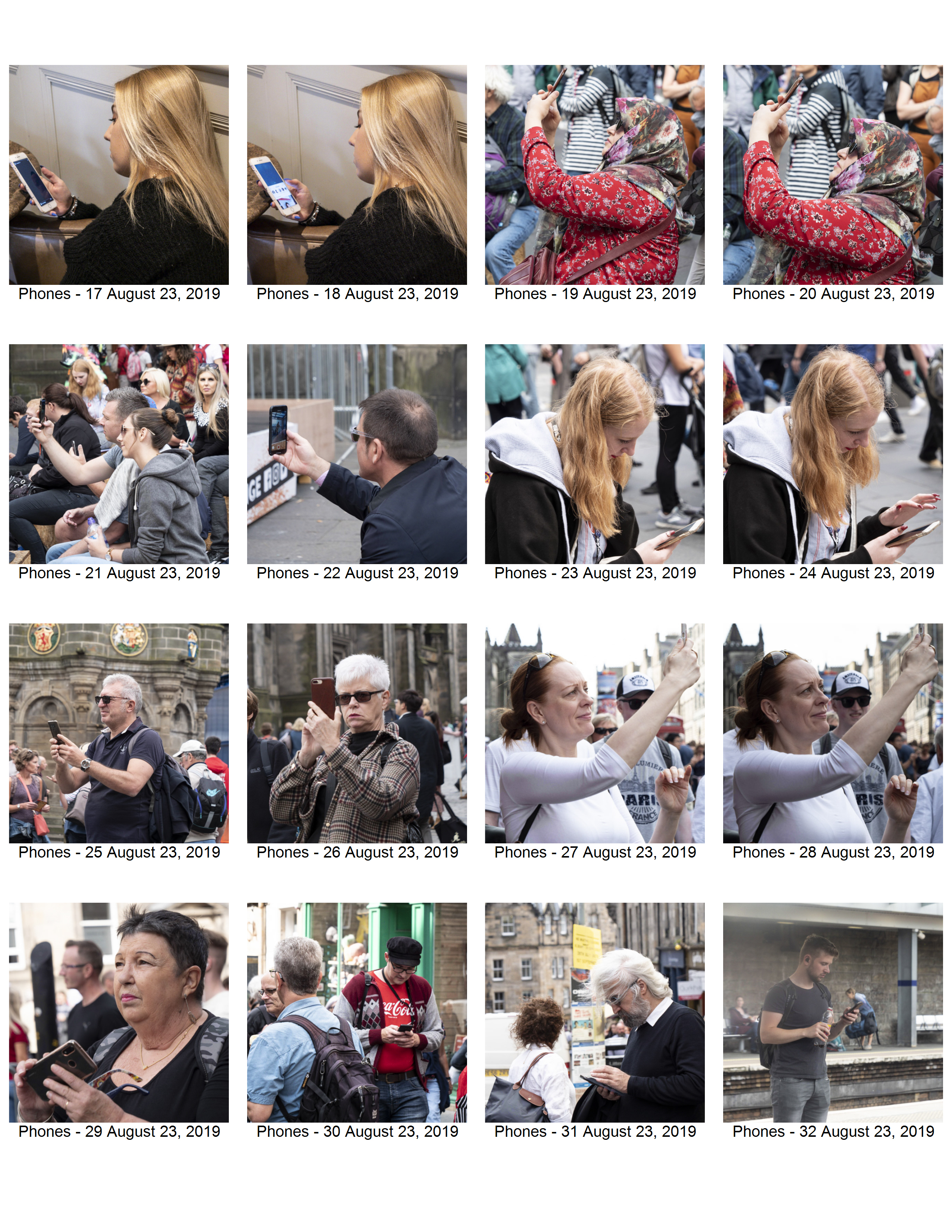

- In this group I had 32 images, some of which were of the same people

- I cut this down to 12 images where the focus was mainly on one person

- I then picked 6 images

- I decided to crop each image to a square

- I then experimented with a black and white or colour image of each.

- I cut this down to 12 images where the focus was mainly on one person

Changing to monochrome helped me to pick out the images that worked best as it helped to clarify the ones where the background was over-intrusive. I also spent time considering the most appropriate processing – but decided that I preferred the colour work in this context.

Final Images:

Summary:

This was an interesting exercise and taught me a lot about candid photography:

- Many of the images I took were too cluttered

- I took too many pictures without enough pre-visualisation

- Most people who saw me just smiled

- Some people can be very aggressive so be prepared to turn away and delete images

- It would be better to go out with a theme in mind, as although I could identify several themes from the images I took, I undoubtedly missed possibilities

- Consider taking from a lower viewpoint to isolate the specific people better

I will probably use this group of images again – but looking at a different ‘theme’.

Contact sheets: