Brief:

The objective of this assignment is to provide you with an opportunity to explore the themes covered in Part Two with regard to the use of both studio and location for the creation of portraits.

This assignment is about taking what has worked from the above exercises and then trying to develop this further in terms of interchanging the use of portraits taken on location (street) with portraits taken inside (studio).

You need to develop a series of five final images to present to the viewer as a themed body of work. Pay close attention to the look and feel of each image and think of how they will work together as a series. The theme is up to you to choose; you could take a series of images of a single subject or a series of subjects in a themed environment. There is no right answer, so experiment.

One of the possibilities I thought about for assignment 2 was to take images of people within their own house, using artificial lighting. My final choice of subject involves this. The room has become the studio. This contrasts with my earlier images for this section which were almost all taken outside with natural light.

Research:

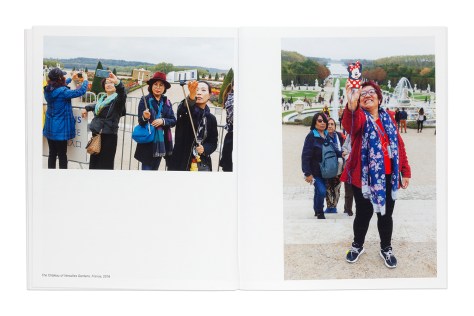

I looked at several photographers portrait work for this including Martin Parr, Christophe Agou, Paul Graham, and Walker Evans and also researched work done taking images of people with disabilities such as Louis Quail in ‘Big Brother’, Siân Davey with her work on her Down Syndrome daughter in ‘Alice’, Polly Bradon’s work with the learning disabled and people with ASD in ‘Out of the Shadows ‘ and ‘Great Interactions’ and Lesley McIntyre’s photoessay on the life of her daughter ‘The Time of Her Life’. I also looked at Diane Arbus’s somewhat controversial work where she took images in a home for learning disabled people (Diane Arbus). There is a harrowing film series done by David Hevey on disability which uses the contrasting images of then and now, to tell a part of the story about disability: see David Hevey – The Disabled Century for more information.

Taking pictures of people who are aware of you is discussed further in Project 2 – The aware and Project 2 – The Aware – 2. Most of the work that I found about people with disabilities either involved people with a learning disability, severe mental health problems, or severe physical difficulties.

Background Information:

This series is about a couple who both have autistic spectrum disorder (ASD). This is a condition (I refuse to call it a disability) that I have worked with for many years and, if I have learned anything, I have learned that the people with ASD and their families are not defined by the label. Each person’s story is different, each family’s story is unique, just as for any other person and any other family. To tell the story properly takes time, a lifetime, both yours and theirs. This is just a snapshot.

Plan:

For this series I took images of a couple with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) and their young child. Janey and Rich were kind enough to invite me into their home and give me permission to use the images. Unlike most of the work on people with disabilities looked at above neither of them has a learning disability. Janey is an author, rarely seen without a pencil and a notebook, and Rich works with computers. Their motto is ‘Anything you can do we can do too’ – although, as Janey went on to explain, that does not include working at a busy supermarket till ( but who would really want to do that from choice).

Practice:

- I met Janey and Rich in their home. It was the first time I had met Rich, so he was naturally somewhat guarded with me, although eventually relaxed. We spent some time talking and then I simply started taking pictures of their interactions with each other, me and their baby. One of the difficulties people with ASD have is with eye contact, especially with strangers and this is evident in all the images.

- I used a combination of natural light, the artificial light in their flat and a flash unit.

- I visualised these images from the start in black and white, partly because it echoed much of the earlier work I had seen and partly because it gives a softer light and timeless feel to the images.

Conclusion:

This was a fascinating piece of work to do. It fits within a much longer work I am planning about the lives of people with ASD and that of their families. I am planning to mainly concentrate on work with adults with ASD as little has been done photographically with this group.

The difficulties were:

- Working inside with limited light

- Allowing enough time for the family to relax without being there so long that I risked overwhelming them

The positive aspects:

- Building a relationship

- Exploring a new (to me) type of way of working

Images:

Learning points:

- Be confident that you can do things

- Relax and the subjects will also relax

- Take enough images to allow for problems with the light

With sincere thanks to Janey and Rich.

Reference list:

Arbus, D. et al. (1978) Diane Arbus. London: Gordon Fraser Gallery.

Braden, P. (2016) Great interactions : life with learning disabilities and autism. Stockport: Dewi Lewis Publishing.

Bradon, P. and Williams, S. (2018) Out of the Shadows. Stockport: Dewi Lewis Publishing.

Hevey, D. (s.d.) Viewing. At: http://davidhevey.com/viewing/ (Accessed on 6 April 2020)

Mcintyre, L. (2004) The time of her life. London: Jonathan Cape.

Quail, L. (2018) Big brother. Stockport: Dewi Lewis Publishing.

Siân Davey (2015) Looking for Alice. Great Britain: Trolley Ltd.