I previously looked at the work of Elina Brotherus when doing CAN while looking at autobiographical portraits (Autobiographical self-portraiture). I have now looked at her work in slightly more detail.

I watched the video of her talk to the OCA students (The Open College of the Arts, 2015) and took notes – the quotes are not exact but give the idea of what she said. It was a fascinating talk and I would recommend it to anyone looking at self-portraiture.

- Brotherus is a Finnish artist, who works between Finland and France. She initially went to France on a residency but didn’t speak any French. She used a post-it sticker method, starting with basic words. Starting with very concrete words and took photos of them in situ. Gradually moved to less concrete words. Did a series of these images. ‘Starting point of my work’. They took me seriously. Then (2011) invited back to work within the schools. Went back to same place as the initial series to look at the beginning of her art – how would it feel? Eventually became a body of work – ‘a position statement’, a turning point, looking back, again using post-its, but talking in more detail. 12 years ago – then a series of statements about how she felt then and where she is now (when taking the images). The images show a picture with long texts, talking about her life – but more about her feelings ‘I can’t take the company of people my own age’. Made into an exhibition and into a book. Includes ‘all the themes that are important to me’, landscapes, fog, reflections, the human figure in a landscape. A return to autobiographical working. Previously was interested in work related to the history of art.

- ‘I don’t do things in a hurry, if you have the luxury of time use it’, leave things aside then come back to them.

- When the work is personal it’s hard to have anyone else there – but when it’s a study of the human figure it can be anybody, it’s easier to position someone else – but when yourself you end up running back and forward. I like to be alone because there are less distractions and I am not worried about the other person.

- I don’t want to hide the camera release – it shows that the person is also the artist – ‘it’s an invitation to a shared contemplation – that’s also why I like the back image’. It’s a different feel when she (the artist) is looking at us or looking away – ‘a frontal figure is a confrontation’. It’s easier as a spectator to enter in (when it’s the back of the artist) as we are together, but we are not disturbing each other.

- The Annonciation– it’s a responsibility as an artist to lift the lid on things that are taboo – pictures can allow you a route into things, making something into a picture may allow you to distance yourself, to see myself as a human being and others have similar issues.

- Work in a sincere way as its all your work, eventually it will all come together, you have your own way of discovering, work more rather than stay at home and think.’ I shoot a lot, then I leave it aside’. Think afterwards, edit and reflect. There is no one right answer, multiple solutions out of a body of work.

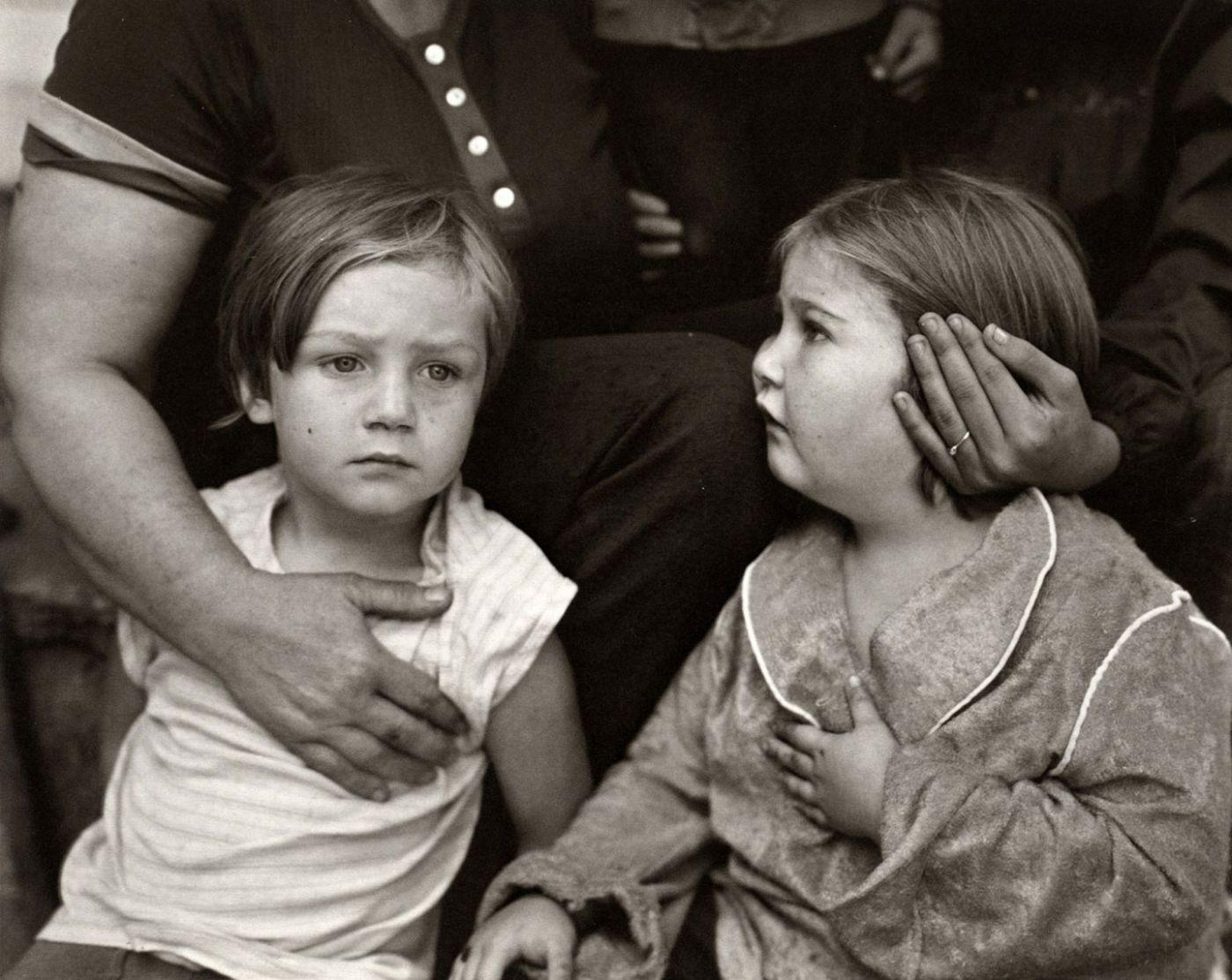

© Elina Brotherus – Le deuil du jeune moi qui a été

I have also looked at more of her work online (Brotherus, 2014). The series discussed above – 12 Ans Après (1999/ 2011 – 2013) shows a combination of her earliest work and the later images taken at the same place. As noted, there are a combination of landscapes and portraits. Interestingly she has mixed portrait and landscape formats for both types of images. All are colour. Most are melancholy. In several the emotions are overflowing. Some, but not all, of the images include the post-it notes, scattered all over the pictures. Unfortunately, I cannot read French – as I think they add another dimension to the work. One of my favourite images from the series is a very simple view of water and sky – La Saône 3.

The series Carpe Fucking Diem is a recent series in which she attempts to move beyond her perceived failure (not having children) looking at ‘the surprising and surreal undertones of the everyday life, not totally deprived of humour, because even an unhappy end is not The End’ (Brotherus, 2014b). While this series is not so overtly autobiographical as some of her other work it still is clearly based on her life and her feelings. Some of it was actually shot at the same time as the work for The Annonciation and the two series can /should be looked at in parallel.

Summary:

I find Brotherus’s work fascinating. When I looked at it previously, I actually found it somewhat disturbing and hard to view. My feelings have changed over the last year and I now find it both sad and surprisingly beautiful. The combination of clear autobiography, both sad and funny, (at times uproariously so) with images of small details, a bowl of potatoes, a worm on the street, give an insight into the life of someone I wish I could meet.

References:

Brotherus, E. (2014a). 12 Ans Après [online] Elina Brotherus. Available at: http://www.elinabrotherus.com/photography#/12-ans-apres/ [Accessed 10 Dec. 2019].

Brotherus, E. (2014b). Carpe Fucking Diem. [online] Elina Brotherus. Available at: http://www.elinabrotherus.com/photography#/carpe-fucking-diem/ [Accessed 10 Dec. 2019].

The Open College of the Arts. (2015). Elina Brotherus student talk | The Open College of the Arts. [online] Available at: https://www.oca.ac.uk/weareoca/photography/elina-brotherus-student-talk/ [Accessed 10 Dec. 2019].