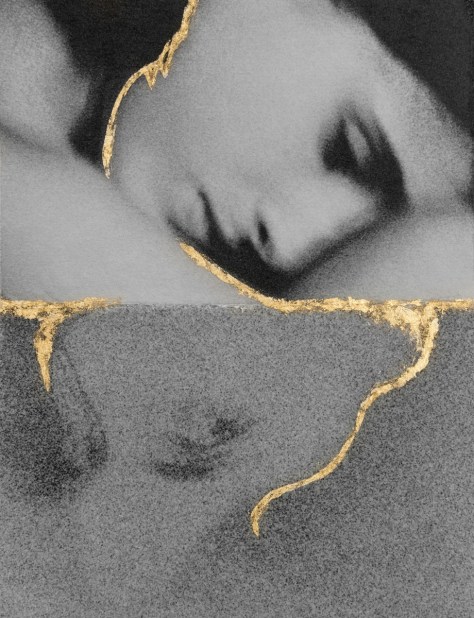

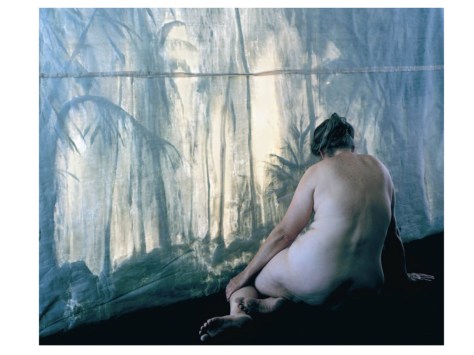

Dayanita Singh’s book Go Away Closer is described as a novel without words, a tale of opposites, connecting personal losses with collective sadness. The series was originally produced for an exhibition, with the images in museum style display cabinets that could be arranged in a multitude of ways. The secondary production in a small photobook of 40 images has, to some extent, confined them, settled the images into a specific configuration. Singh does not add any text or titles to explain the meanings. In an interview Singh has said that she actively ‘withholds’ narrative information (Rafa, 2013). The images are a selection of portraits, empty interiors, and close ups. Some, like the starting image in the book,a young girl lying on a bed, are acutely personal, other like the ending image of wet pavement, seem distanced. There is no story other than an overall feeling of change and despair, loss and mourning. But I am not Indian. Maybe the images would not read that way to someone from her culture. In an interview or the Guardian Singh says, ‘Go Away Closer is what happens between people: I can’t live with you, I can’t live without you’ and also ‘that there was a more interesting way to edit photographs – not through an obvious “theme” but through what’s going on intuitively or subconsciously’ (Malone, 2013).

Singh has moved from creating fixed exhibitions to what she calls her ‘museums’. These consist of groups of related images that are placed within wooden structures of 30 – 40 images, but these can be changed out for other images, and she may change them even within a single show. The set becomes a reflection of her feelings at the time, not a constant and unchanging one.

Her online blog (Singh, n.d.) made fascinating reading giving advice to new photographers, details of her thought processes about the development of her museums and writings about her work from others. The letter by Rilke that she quotes gives very pertinent advice to anyone engaged in a creative process, but especially to anyone lacking confidence in their own self worth as an artist. ‘So, dear Sir, I can’t give you any advice but this: to go into yourself and see how deep the place is from which your life flows; at its source you will find the answer to, the question of whether you must create. Accept that answer, just as it is given to you, without trying to interpret it. Perhaps you will discover that you are called to be an artist. Then take that destiny upon yourself, and bear it, its burden and its greatness, without ever asking what reward might come from outside. For the creator must be a world for himself and must find everything in himself and in Nature, to whom his whole life is devoted.’ (Rilke, 1934).

Reference list:

Malone, T. (2013) ‘Dayanita Singh’s best photograph – a sulking schoolgirl’ In: The Guardian 10 October 2013 [online] At: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/oct/10/dayanita-singh-best-photograph-schoolgirl

Raza, N. (2013) ‘Go Away Closer’, Dayanita Singh, 2007. At: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/singh-go-away-closer-t14176 (Accessed on 20 April 2020)

Rilke, R.M. (1934) Letters to a young poet. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Singh, D. (2007) Go Away Closer. Göttingen, Germany: Steidle.

Singh, D. (s.d.) Blog – Dayanita Singh. At: http://dayanitasingh.net/blog/ (Accessed on 20 April 2020)