Taking portraits of people who are unaware of you needs a certainly needs a degree of stealth and a place where there are plenty of people who are engaged in their own thoughts. One of the commonest places for this to be done is on public transport. If you google ‘images of the underground in London’ it becomes obvious that this is a very common place for photographers to take pictures. Many of these are of the underground architecture, others are of general crowd scenes and yet more are portraits, usually taken without the knowledge of the people being photographed, although some are obviously posing for the camera.

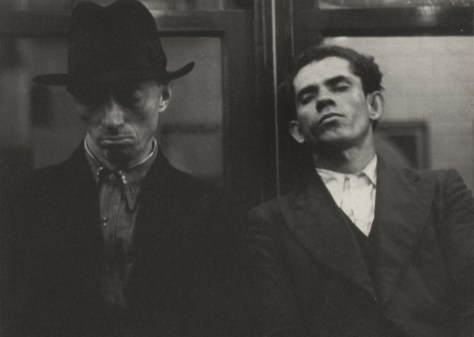

The genre probably started with the subway images of Walker Evans, although similar portraits were also taken by Helen Levitt, who was his apprentice, at much the same time. The two of them often went out together as Evans thought that people were less likely to see him taking photos if he was with someone else. Levitt revisited the subject much later in 1978 taking a range of images of similar scenes, this time against a background of graffiti (Silverman, 2017). They can be seen in Manhattan Transit: The Subway Photographs of Helen Levitt.

Stefan Rousseau, a London photographer also took images on the London Underground. There is a recent photoessay available on this in which he says ‘Suddenly I became aware of a new world of phone-obsessed, sleep-deprived, makeup-wielding commuters so absorbed in their own world that I felt I had to photograph them. I’m astonished by the skill of the women who are able to apply their makeup while hurtling through tunnels and those who can watch last night’s TV standing up in the smallest of spaces’ (Rousseau, 2019). The whole essay can be accessed at:

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/mar/29/riding-the-tube-a-photo-essay-by-stefan-rousseau

Lukas Kuzma is another photographer who has taken pictures on the London Underground in the series Transit (Kuzma, 2015) in which he shows a mixture of images of people, some aware of him, others clearly unaware. Some of his images are amusing, some fascinating, others almost cruel. Some of his images can be seen on Behance.

For other photographers who work on images taken on public transport see: Martin Parr Christophe Agou and Walker Evans

Edited 04/11/19:

I have just come across another photographer who worked extensively on the London Underground in the 1970’s. Mike Goldsmith has just produced a book London Underground 1970 – 1980 which shows images from a slightly earlier underground scene, although the people have similar world-weary expressions. The pictures can be seen at:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/in-pictures-50261478

Given the number of articles and relevant photographers I have found in a fairly short exploration of this topic, I suspect that a whole PhD could be written on it.

Reference list

Candid moments on the London Underground. (2019). BBC News. [online] 4 Nov. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/in-pictures-50261478 [Accessed 04 Nov. 2019].

Kuzma, L. (2015). Transit. [online] Behance. Available at: https://www.behance.net/gallery/23661963/Transit [Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].

Levitt, H., Campany, D., Hoshino, M. and Zander, T. (2017). Helen Levitt – Manhattan Transit. Köln Galerie Thomas Zander Köln Verlag Der Buchhandlung Walther König.

Rousseau, S. (2019). Riding the tube – a photo essay by Stefan Rousseau. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/mar/29/riding-the-tube-a-photo-essay-by-stefan-rousseau [Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].

Silverman, R. (2017). The Subway Portraits of Helen Levitt. [online] Lens Blog NY Times. Available at: https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2017/10/12/the-subway-portraits-of-helen-levitt/ [Accessed 20 Aug. 2019].